Filipino Foodways in the Triangle: Resistance, Community-building, and Power in the American South

- ashlee monton

- Sep 13, 2022

- 35 min read

Updated: Sep 21, 2022

This project was funded by the Center for the Study of the American South and Southern Futures at UNC Chapel Hill.

“There’s not a lot of us here,” my consultant Dina shares as we speak about Filipino presence in North Carolina’s Research Triangle. I share her sentiments as a Filipina doctoral student in a predominantly white institution. As she invites me into her home, we co-create a space protected by the familiar smells of our own food and language of our own people, and suddenly, we no longer feel the need to be anyone but Filipino.

This project examines Filipino foodways as a mode of resistance in the face of the Otherness that Filipino Americans experience in the American South. Foodways research is concerned with the “practices, rituals, and customs surrounding all aspects of food preparation, consumption, and disposal” (Ho, 2004:45). By documenting and analyzing foodways practices and processes within the Filipino-American population living in the Research Triangle, I address how food becomes a space of refuge for Filipino-Americans in the South—in a region that has historically neglected Asian American lived experience. I align my work with scholars who have utilized foodways in a critical manner, in ways that expose issues rooted in power dynamics, colonialism, and defiance through food. As food scholar Mark Padoongpatt urges, the critical analysis coming from the lens of foodways is vital in humanities discourse as it “demonstrates how social hierarchies of power have been inscribed on bodies by categories created and maintained by other human senses besides sight, namely, taste and smell” (2013: 186).

Using food as a lens through which to examine “everyday” acts of resistance in the lives of Filipino Americans in the South deepens understanding of foodways as “a field of social action” (Douglas, 1972:5). Using food as a lens through which to study culture, history, race, and gender, foodways has emerged as a vital area of study out of multiple disciplines --English, anthropology, sociology, history, film studies, and gender studies (Ku, 2013). This research recognizes how food is one of the tools with which Filipino Americans have fought against colonialism, imperialism, and erasure. As food scholar Doreen Fernandez states, “for Filipinos/as, since the American colonial times, food has been a vital field of study – even only as a vestige of war, as an index of struggle” (2002: 241). Through original oral history and archival research, I investigate how Southern Filipino Americans resist feelings and experiences of Otherness, reclaiming their identities from their colonial past through engagement with Filipino food traditions. As Osayi Endolyn writes in her essay “A New Normal South,” “For people whose Southern identities have been inherited rather than forged, the question of belonging may feel overwrought. It’s not. This distinction is easy to overlook when you have made your life the place that you’re from, or if you’re not immediately interrogated for characteristics that set you apart from your neighbors” (2020: 5). In the case of Filipino Americans in the South, regardless of whether their Southern identity was inherited or forged, the question of belonging carries heavier weight. To be Filipino in the South is to occupy a permanent state of racial Otherness -- not fully claiming an Asian American identity nor a Southern identity.

Notions of what constitutes a “Southern” identity also complicate this study. The South has a tumultuous, racist past, and the violence against black and brown bodies during the Confederacy is a permanent scar. It is evident that these scars have not healed as we bear witnesses to the everyday violence that people of color experience through racial capitalist institutions like the prison industrial complex, not just exclusive to the South. Why, then are these myths of the South as the only bearer of historical trauma been continually perpetuated? As Michael Twitty writes, “It’s a misnomer, the Old South. The South has never been still, or merely aged. It is not stagnant and it is not as set in its ways or physical boundaries as much as some would like to pretend” (2017: 22). The South, and by extension, Southernness, is not absolute.

This project addresses the following questions: How do Filipino Americans in the South navigate both Southern and Filipino identities through expressive means? How might Filipino foods and foodways traditions challenge the timelessness and normativity of the South, and Southern food? And, how might the feelings of Otherness by Filipino Americans in the South add more nuance to the relative invisibility embedded in the everyday lives of Filipinos in the U.S., more broadly?[1]

Drawing upon historic oral history interviews, and recording original ones, I document the social experiences of Filipino Americans in the Triangle to challenge ideas of who “belongs” in the South. Indigenous historian Nepia Mahuika contends that oral history “is a matter of power and liberation as much as it is a process of revitalization and preservation”(2019: 41). I consider oral history a necessary method in my research for the survival of Filipino American history. Filipinos have fought the long fight against their invisibility, especially in narratives of American history. Contributions of Larry Itliong and other Filipino farmworkers who aided Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta in the Delano Grape Strike in the West Coast are glossed over, despite the fact that Itliong spearheaded the initial phase of the strike, eventually convincing Chavez to organize the Mexican farmworkers.[2] Fred Cordova, founder of the Filipino national Historic Society has referred to Filipinos as the “Forgotten Asian Americans,” alluding to the erasure of Filipino voices within Asian American history, and arguably, within American history as well. The voices of Filipino Americans in the South are often ignored and underexplored in the fields of Southern Studies, American Studies, Asian American Studies, and Critical Filipinx Studies.

I believe that recording oral histories of Filipino Americans is crucial to the creation of a whole and accurate picture of American historical experience. The narratives of Filipino Americans in the South contribute a dual purpose to the distinctive racial experiences of Asian Americans in the South. For example, Rhesa Versola’s recorded oral history archived in the Southern Oral History Program Collection at the University of North Carolina reflects these distinct experiences as she speaks about Filipino visibility in Raleigh, North Carolina:

It was such a weight, such a burden, to have to explain, almost at every turn, “No, I am not Chinese, I am not Japanese, I am not Korean.” “You’re Hawaiian, you’ve got to be Hawaiian.” I’d say, “That’s closer, I have a lot of relatives in HI, but I’m from the Philippines. No one would know what that was…

Rhesa Versola, along with other Southern-Filipino Americans I have interviewed in this research, experience a kind of marginalization that is unique to Filipino Americans in the South: What does it mean to be Othered while already existing in a permanent state of Otherness? It is Rhesa’s constant experiences of having to talk about her race and ethnicity in any given moment. Further, her being categorized as either Chinese, Japanese, Korean, or Hawaiian, but never Filipino, echoes the same question that all people of color experience: “But where are you REALLY from?”— a symptom of what bell hooks calls “imperialist nostalgia” (2014: 22). In “Eating the Other,” hooks defines this as a sort of morbid curiosity from the dominance of white heteronormativity. She expresses these everyday racially-charged interactions from the “Other,” like Rhesa’s, as follows,

This longing is rooted in the atavistic belief that the spirit of the “primitive” resides in the bodies of dark Others whose cultures, traditions, and lifestyles may indeed be irrevocably changed by imperialism, colonization, and racist domination. The desire to make contact with those bodies deemed Other, with no apparent will to dominate, assuages the guilt of the past, even takes the form of a defiant gesture where one denies accountability and historical connection (2014:25).

The desire to figure out Rhesa’s ethnicity may well be an innocent question posed, but when one looks at the power structure embedded in those questions, it becomes less of an innocent question and more one that reveals the everyday marginalization of the Other. Further, this Otherness becomes more political when one looks at the history of racialization that Filipinos have experienced in American history. In White Love and Other Events in Filipino History, Filipino historian Vicente Rafael argues that:

On the one hand, [Filipinos] are racialized in the United States as nonwhite or are equally problematic as Asian-Americans, so that their American-ness is constantly under question. On the other hand, they are attached to the political and symbolic economies of the United States such that their “Filipino-ness” remains of dubious authenticity to Filipinos in the Philippines (2000: 24).

The tension between Filipino-ness, Asian-ness and American-ness is an everyday experience for Filipino Americans. Rhesa’s experiences of hyper-visibility and invisibility is emblematic of this tension. Further, such complexities of racial boundaries are exacerbated by the fact that there is little scholarship centering Filipino American voices in the South. In the Southern Oral History Collection at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, there are fewer than 10 oral histories of Filipino-identified individuals, despite the fact that 16.3% of the Filipino American population resides in the South, following the West Coast, Hawaii, and the East Coast. Nadal argues that research on Filipino Americans is concentrated heavily in the West Coast and Hawaii, but not so much in the South, despite the growing Filipino communities in this region (2011).

As a Filipino American in the South, I attach myself to this work. The love-hate relationship I have with my place in this region has opened me up to the core of my Filipino-ness. Moving from Los Angeles, California, in 2020, I thought I had an understanding of what my Otherness meant, as a Filipina, but living in the South comes with many challenges. I did not realize how much I ached to run into someone that looked like me in public, to hear somebody speak in Tagalog in a casual conversation at the store, or to simply be around people whom I never had to explain what or where Filipinos came from. It was this ache that led me to this work. Together, my consultants and I reckon with our Otherness, but at the same time, forge the path to resistance by forming our community one Filipino meal at a time.

METHODS

For this project, I listened to all seven of the archived Filipino-American oral histories in the Southern Oral History Program Collection at UNC-Chapel Hill. Of these voices, Rhesa Versola’s directly inspired me. I use her oral history along with three original oral histories that I have conducted. I contextualize these interviews with the ethnographic fieldwork I conducted in Filipino restaurants/homes in the Research Triangle in 2020-2021. This capstone project is the first stage of my larger dissertation project.

Informed by Nepia Mahuika’s indigenous perspective on conducting oral history, I structured my interviews with non-oppressive methods. As Mahuika contends, “In defining oral history on our terms, these contests are not post-colonial but are presently engaged in on-going decolonial struggle, reclamation and liberation” (2019: 4). With that in mind, during the interview process, I employed a collaborative approach that involved the sharing of my own experiences as a queer Filipina living in the South. Focusing on local Filipino communities in the Research Triangle area, I locate this research in restaurants such as Filipino Express Restaurant in Raleigh and MediterrAsian Bistro in Durham—some of the few places that reveal this community’s place-making in the South. Further, this Filipino place-making is also present in the homes of the consultants I have been working with in this project. Future research will expand into additional Southern sites of Filipino place-making.

I interpreted all interviews through the lens of Pinayism, a decolonial Filipina feminist lens that centers the voices of the Filipino community. Interviews were in Tagalog/Bicol/English and lasted for an hour each. Consultants were a mix of first-generation and second-generation Filipinos living in the Triangle, and explored the diverse social and cultural significances within Filipino food traditions, some of which have remained unchanged across generations. This project is also informed by Kapwa – Indigenous Filipino knowledge that emphasizes the shared relationship of the self and of the community. It is translated loosely as “fellow being,” and according to Filipino theorist, EJR David, it is “one's unity, connection, or oneness with other people- regardless of “blood” connection, social status, wealth, level of education, place of origin” (2017: 48). In addition, my practice of kapwa goes beyond the realms of conducting this project, as I continue to strengthen the bonds that I have with my consultants for the course of my life. Weaving together this relationship between myself and my consultants becomes vital to revealing the connections between resistance and colonialism. Food, especially, ethnic foodways, signifies resistance and resurgence for those who were historically silenced (Muñoz, 256). Additionally, kapwa, illuminates the ways that food becomes a site of ownership and resistance for this community. Foodways can be an essential lens through which we trace the path to resistance.

WHY FOOD?

Historian Hasia Diner notes that, “Foodways include food as material items and symbols of identity, and the history of a group’s ways with food goes far beyond an exploration of cooking and consumption… It amounts to a journey to the heart of its collective world” (2001: 9). In this research, I use foodways as a framework for understanding the placemaking practices of Filipino Americans in the South, as a point of reference with which to understand Filipino American history. During the American occupation, Filipino dishes and food practices were denigrated and deemed uncivilized, reflecting its people. Archival records show that many reformers focused on food to civilize their “Little Brown Brothers” (Choy, 2016: 35). Although food was utilized as a colonizing tool, the late Filipino historian Dawn Mabalon recalls that community formation and cultural preservation was integral in the plight of one of the first Filipino American communities based in Stockton, CA. Furthermore, she adds that the fusion of Filipino-American food was central to this community’s survival: “the unique Filipino/a American cuisine they created was a powerful symbol of their collective struggle to survive despite overwhelming odds” (2013: 148). I extend this understanding of foodways as a space of resistance for Filipino American communities in the South as they navigate this region. Food becomes an avenue of “everyday” acts of resistance in the lives of Filipino Americans in the South. This resistance is present in the homes of the consultants I have worked with as well as Filipino restaurants in the Triangle like MediterrAsian bistro, capturing the essence of Filipino food culture despite their invisibility in the South.

Robert Ji-Song Ku argues that, “understanding and apprehending Asian American food experiences begin and end with the body” (2013:1). Why do we so often link Asian American identities with their placement in the American food landscape? To understand this imagery, think of your local grocery store. Why do we have to locate Sriracha in the “ethnic” or “international” food aisle, rather than in the aisle with all the other hot sauces? Understandably, this is a very simplistic way to view racialization and categorization but it broaches a conversation about what mainstream Americans consider “exotic” or “normal” food, and by extension, people. In Rhesa Versola’s oral history, she recounts her daughter’s uncomfortable experience: “I remember my daughter came home just a couple of months ago and she said someone asked what she was eating for lunch. ‘Is that dog?’ What?! So mean. So ignorant.” The intersection of food and race discourse centers this project, more broadly.

Ji-Song Ku further notes that, “the category Asian American is a historical U.S. federal census designation that rests in part on the long history of what might be described as the Foucauldian control and discipline around the movement of Asian bodies to America, in part on their toil in various agricultural fields and plantations, fruit orchards, fisheries, and salmon canneries in Hawai‘i, California, the Pacific Northwest, and the South” (2013: 1). It is important then to realize that the relationship between food and the racialization of Asian Americans, which also include Filipinos, was not some byproduct of some natural migration patterns. In fact, foodways can be a vital lens with which we can understand effects of U.S. imperialism, colonialism, and racialization.

FILIPINO AMERICAN HISTORY

The Filipino community’s colonial history (by Spain, the Japanese, the British and the United States) has made them a permanent vestige of Otherness and erasure both politically and culturally, despite being the second largest Asian/Pacific islander community in the U.S. As historian E. San Juan Jr. writes, “the reality of U.S. colonial subjugation and its profoundly enduring effects - something most people cannot even begin to fathom, let alone acknowledge, has created the predicament and crisis of dislocation, fragmentation, uprooting, loss of traditions, exclusions, and alienations for Filipino Americans” (1994: 206). Invisibility is an indelible mark that the community carries. Moreover, Filipino American experiences get lost within the realms of Asian American experiences. Ocampo writes, “Previous scholars have highlighted Filipino Americans’ cultural and political marginalization since the inception of pan-Asian identity in the 1960s, citing their distinct colonial history and socioeconomic patterns as explanations” (2013: 296). Further, studies have shown that Filipino Americans are more likely to experience racial microaggressions than East Asians (Ocampo, 295). This marginalization is even more apparent when we look at how Filipinas, or Filipino women, whose labor of care in the form of nursing and caregiving is exploited globally by imperial powers such as the United States.

Critical Filipinx Studies was born from the struggle to be visible, both in theory and praxis. In this field, Filipino American history is at the forefront, emphasizing the retelling of the community’s experiences from their voices. Mabalon argues that Filipino American history is often misrepresented in the field of Asian American history (2013). Filipino Americans are the third largest Asian American population in the U.S. 2019 Census data reports that two-thirds of Filipino Americans reside in the West Coast, 16.3% live in the South, 9.7% in the Northeast and 8.4% in the Midwest. Much attention has been focused on studying Filipino Americans in the coastal areas, but not much on Southern Filipino Americans. Though lesser known, the Filipino community has always had a historical relationship to the South, as historian Marina Espina writes. During the Spanish Galleon trade, Filipino seamen traveling from Manila to Acapulco decided to abandon their posts and establish a fishing community in Saint Malo, Louisiana (1988: 77). This was the first known Filipino community in the South during the 19th century. In the present, the population is ever-growing in the South with communities residing in Virginia, Texas, Maryland, and North Carolina, to name a few (US Census and NCAA Census). Southern Filipino American experiences would add more nuance to the growing literature focusing on Filipino American experiences. Further, I argue that Southern Filipino American voices are distinct in that they face different racial experiences due to the mythical notions of the South. This then allows us to prod ideas of visibility and invisibility even further, taking into account the ways in which Southern Filipino American experiences are untold within Critical Filipinx Studies.

FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS

In my ethnographic fieldwork from 2020-2022, I was privileged to be invited into the homes of many community members across the Triangle, while also interacting with community members in Filipino restaurants like MedditerrAsian. I consider myself an insider and an outsider simultaneously as I am Filipina American but not from the South, like the consultants I have worked with. In the conversations we had, people helped me understand what Filipino-ness meant in the South. Theirs was an active decision to always be in touch with their roots whether through language or food, and to find their community and hold on to it for dear life. Three themes emerged from our rich conversations: Otherness, Resistance, and Homecoming. This project is a first portion of what I hope to continue to produce with and for my community in the future. As I recognize the small community that I have created through this research, I look forward to continuing these conversations with my community in other parts of the South for years to come.

OTHERNESS

Rhesa Versola immigrated to Brooklyn, NY in 1969 when she was 3 years old. Her father, a medical student, applied for a US Visa and brought his entire family to the States. In 1970, her family moved to Raleigh, NC. Growing up in Raleigh, she recounts having a difficult time at school due to the casual racism she faced on the regular. She recounts,

“I was sitting in my history class and we talked about Pearl Harbor and the kid behind me leaned over, I could feel him close to my shoulder, and he said, “Why did you do it?” And I thought [laughs], “I’m not even Japanese! Why are you asking me this question?”

Otherness is embedded in the everyday lives of Filipinos. Especially with Filipinos in the South, whose communities are smaller in comparison to their counterparts in the West or East Coast. Further, this is complicated by different ideas of Asian American racialization within this region. Trisha, my consultant, recounts an experience similar to that of Rhesa:

One time I was walking down the street. And yeah, dude, like a dude who was, I don't even know he was like, it is this weird person you would normally not talk to. He was like - he followed me for a few blocks and he was just like, “Excuse me, like, I was trying to figure out what you are. Are you like Hispanic or what?” I'm like, what? And then I had to be like, “Okay, I'm Filipino. The Philippines is here on the map. This is it.”

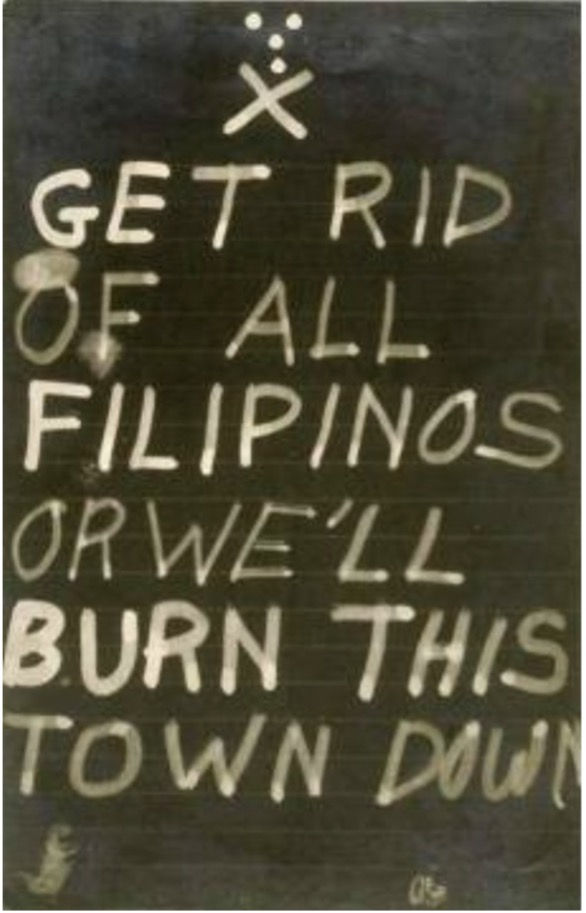

The everyday experiences of racialization and Otherness becomes something Filipinos encounter and expect. This notion of hypervisibility and invisibility is nothing new, when we look at anti-Filipino sentiments in American history. After WWII, about 100,000 Filipinos resided in Hawai’i and California. The outflow of Filipino communities in California came with the backlash of white communities. To the point that their presence in Taxi dance halls dancing with white women started a riot (Burns, 2013). The growing resentment over the Filipino community also encouraged many businesses to ban them. Below are some of the public-facing signs that portray the exclusion and racial violence that Filipinos experienced:

Figure 1, "Positively No Filipinos Allowed" in a storefront in Stockton, California, 1930. From Images of America: Filipinos in Stockton (2008) by Dawn Mabalon and Rico Reyes

Figure 2. "Get Rid of All Filipinos or We'll Burn This Town Down" sign. From Images of America: Filipinos in Stockton, (2008) by Dawn Mabalon and Rico Reyes.

The outright exclusion of Filipinos documented in American history reflect the continual exclusion that Filipinos encounter in the present -- such is evident in the statements by Rhesa and Trisha. More importantly, this exclusion is exacerbated by the complicated ideas of race in the South, and in America. Rhesa adds,

Eighth grade. I was 13. I had my first pair of Levis. Thirteen is not a great age no matter black or white, but being the only “other” in town, that made it particularly bad. I do remember in the first semester there in eighth grade in the school yard having a group of black girls pulling on one arm and a group of white girls pulling on the other arm, saying that I had to choose. Was I black, or was I white? Because they couldn’t—that’s all they knew.

This idea of having to be one or the other -- “black” or “white” prompts an ongoing discourse on racialization and Otherness. Further, Rhesa explicitly stating this overwhelming feeling of knowing she did not belong to either helps us understand Otherness as it is experienced by someone who was both Southern and Filipina. What did it mean to occupy those spaces? To Rhesa, it meant having to carve out a place for herself despite not belonging to any category, but “other.” She continues this negotiation by recalling the advice that her parents gave her, “I remember as a kid, my parents always told me, “Don’t rock the boat. Blend in.” I’m like, “How can I blend in? I’m the one sticking out.” Rhesa began to question her parents’ wishes when the world around her forced her to become aware of her marginality. Her saying “I’m the one sticking out,” was the knowing that she will always be hypervisible due to her Filipina identity. My consultant, Trisha, and Rhesa’s everyday experiences of microaggressions reveals to us that race becomes an inescapable mark that Filipinos carry. Filipina theorist and activist, Linda Pierce in “Not Just My Closer: Exposing Familial, Cultural, and Imperial Skeletons,” reflects, “Being a Filipina-American, or Pinay, means being colonized – first by Spain, and then by the United States -- and although you may not have been alive or present for the process of colonization, you experience the fall out nonetheless” (2005: 31).

RESISTANCE

Filipino foodways raise issues around belonging and difference in the broader context of American racial inequalities. As Dina reflects, “American food is part of the American dream, I guess. Back home I remembered being socialized that American food was just better. But when I moved to the U.S., I just never felt satisfied with American food, nothing compares to the feeling I get when I have Filipino food.” The way that Dina associated American food with the American dream reveals that the era of colonialism is not just a distant past. In the colonial period -- especially during the American occupation, Filipino food was deemed “disgusting” according to many of the American reformers during the American colonial period, as Orquiza (2020) contends. Food became a colonizing tool that the imperialist used to control the Filipino people. American reformers in the Philippines now had a mission to erase the Filipino way of life, and replace it with their own, for the purpose of modernization and the ever so loaded term, “civilization.” In a statement by American military captain Jacob Isselhard on the traditional Filipino way of eating with the hands, he retorts,

In exact accord with many other primitive methods and customs of the Filipinos, is also their mode of eating. There is no evidence of chinaware, knives, forks, or spoons, not even of tables or chairs in the majority of Filipino homes... Table manners are unknown and, well, hardly required as everyone helps himself, securing the food with his (or her) natural five-pronged fork—the hand (Orquiza 2020: 30).

The denigration of Filipino food, as well as Filipino food practices have introduced this value system that has categorized the “Filipino” as primitive and the “American” as modern. However, despite this erasure and subjection, the Filipino community has found ways to take back ownership of their culture by virtue of resilience. Going back to Dina’s reflection, she has realized upon moving to the U.S., that Filipino food will always give her these feelings of satisfaction and happiness. These moments of taking back the narratives can also reveal to us the many ways in which historically silenced communities, such as the Filipino community, create a space for themselves and resist the cyclical effects of colonialism.

Some Filipino dishes have captured the resistance from the histories of their colonial past. One such example is Filipino spaghetti – not any different than your typical red tomato sauce and spaghetti pasta noodles, but it is the added sweetness from sugar mixed in the sauce, the chopped hotdogs, and the melty, grated cheddar cheese on top that makes it Filipino. It is almost always enjoyed with a serving of fried chicken. It is this combination, as well as the symbolic meaning behind this dish that is worth exploring. Though Dina did not prepare Filipino spaghetti and fried chicken in our communal feast, the message remains the same: Despite colonial trauma, communities can still persist, survive and form their own traditions.

Dina has helped me better understand the ways in which food can be a space with which one can resist these subjecting forces. She expresses the ways in which the lack of ingredients does not stop her from cooking Filipino food in the South, in fact, it has allowed her the creativity to improvise.

Here in the U.S., I had to learn on my own. I had to learn how to improvise. Improvising ingredients, improvising recipes, improvising tastes. Like say for example. when you prepare Natong. First of all the gata -- is fresh in the Philippines. Meanwhile, out here, the coconut milk is sold in a can. It is not really that authentic but I would rather have it than not be able to enjoy having Natong. It might not taste like the one at home, but at least I can still enjoy it, and the fact that I prepared it.

In the process of how Dina prepares her traditional Natong, she is preserving and representing Filipino culture in a space where she feels detached from her community and her roots. This is also similar to that of Don’s mother’s improvisation with collard greens in the dish, Laing. The simple act of improvisation and creativity becomes an act of resistance, just like how the Filipino community has reimagined Spaghetti and Fried Chicken.

Dina also offers a different way in which we can look at food, something that is more than sustenance, but filled with so many deeper, personal meanings. She contends,

Filipino food reminds me of home. It’s just comfort. It just makes me feel secure. Like I know my roots, and I can always come back to it. I know that wherever I am, when I make Filipino food, I’ll always be transported back home. My palate is what brings me back home. I can always take that with me wherever I go.

The space with which food exists in, especially in migrant communities, is more than an objective necessity. In Dina’s case, Filipino food reminded her of where she came from. Her “palate” was her connection to her roots, and it was something she held close to her heart regardless of her immigration journey. Rhesa asserts a similar sentiment when she talked about the pressures of assimilation:

They made a conscious decision not to continue speaking to us in Tagalog or Ilocano. Ilocano was the local dialect where we were from, the same area that Ferdinand Marcus was from. But we didn’t speak anything but English at home. The only times I even heard my parents speak Tagalog or Ilocano was when we were other relatives or friends from the Filipino community in Raleigh. I always knew when Mom and Dad had been talking to relatives on the phone because their accent became so much thicker when they spoke English again. That was something that they already started to take away from us. Because if we were going to stay in the U.S.—that we were stuck in America—they wanted us to assimilate as quickly as possible. So we got the awful shag haircuts of the time, we wore the matching pantsuits at this time. Terrible, looking back at the pictures, I think, “Why did you do that to us?” Trying to quickly assimilate us into the American culture. Yes, we were cut off [because of Martial Law in the Philippines, footnote] The food was the only other connection to our culture. Our dress changed, our language changed…

Rhesa recalls being “cut off” from her culture, due to the pressures of assimilation. Though, she took refuge in the fact that food was a significant connection that stayed with her and her family. Dina and Rhesa communicate a deeper meaning when it came to food, as it was the only accessible thread with which they could connect themselves to their roots. Trisha communicates this connection as she speaks candidly about what Filipino food means to her: “It [Filipino food] is definitely like a tie to like, it’s like a shared understanding, a shared cultural understanding. It's very much tied to memories of parties and going to family members' places and just being cooked by people. You know, it's very personal to me.”

Additionally, she adds that the performance of cooking Filipino food also becomes an act of keeping traditions alive, attaching it to somewhat of an organic action driven by taste, smells, and oral tradition:

“Cooking Filipino food is like… it's less of like, sometimes I follow recipes. Oftentimes it's more of like, going by the taste that I know, and then I guess that's how it was taught to me. Like, doing things by taste and approximation and stuff. So um, I think that's a little bit informed by how I eat. And so when I cook it [Filipino food], I don't feel like it's less of a threat. I don't know, like it's more just an organic thing. And I do always kind of remember how like, like, for instance, like my dad always taught us how to gisa, you know, to do the garlic, onions and ginger in the oil first. And also, it's funny that I’m always like telling somebody else a long time ago that I didn't realize what the English word for gisa means.”

Trisha brings up the process of gisa, as one of the main components of Filipino cooking that she inherited from her family. Gisa is performed by chopping up flavorful and fragrant ingredients like garlic, onions, and ginger, for instance and sauteeing them in a hot pan. It is the first step to every Filipino dish, as she recalls from her father’s instructions. The symbolic notions of gisa and how it was passed down to her from her father is emblematic of a kind of cultural preservation. Food, then can be a transmitter of traditions, allowing these traditions to be kept alive for generations to come. Further, she also brings up the notion of Filipino food being something that comes to her organically, as she lets her palate guide her through the process. Even though she does not have access to the usual Filipino food being prepared by her family in California, she makes her own version in her home in Durham, North Carolina. Additionally, Don recounts the specialness of Filipino food and its cultural significance,

I do think there is something distinctly Filipino in our food culture and how it is evidence of a connection and a belonging to our community… and even as a diaspora member who has family around the world and also still in the Philippines… food is also the connection there like when we send the balikbayan box, the important things are the food, like candies, and etc.

Filipino food prompts feelings of belonging, return, and even transnational links, as Don categorizes the “distinctly Filipino” description of the food culture. Further, it can be said that Filipino food acts as vessels of cultural preservation. Rhesa contends that she makes sure her second-generation children experience Filipino culture, “My kids get exposure through relatives and especially through food.”

As Lucy Long contends, “The materiality of food, its dynamic and unstable character, its precarious position between sustenance and garbage, its relationship to the mouth and the rest of the body, particularly the female body, and its importance to community, make it a powerful performance medium” (2015: 233). It was utmost importance for Rhesa to transfer these cultural meanings to her children, whether it be through elders or the food. This care in preserving the Filipino culture is arguably, a performance of resistance in itself.

My consultants’ intimate connections with Filipino food are evident in the ways they describe them. Feelings of home, comfort, and identity are interwoven with simple Filipino dishes they prepare at home. The sensory feelings from their “palate” awaken feelings and emotions that are sometimes hard to place. Bernard Herman calls this “terroir,” signifying “the particular attributes of place embodied in cuisine and narrated through words, actions, and objects” (2009: 37). Further, he adds that “Place alone, however, fails to translate the deeper associations that terroir projects about identity” (2009:37).

With Dina, her palate brings her back to the Philippines, despite being 6,000 miles away. Her process of food-making, and food-eating not only connect her to the Philippines, but it connects her to her identity. As Behar contends, “the body is a homeland -- a place where knowledge, memory, and pain is stored” (1996:154). With this in mind, the palate, which is accessed through food, becomes a one-way ticket back home. Our conversations about food, identity, and community have opened up my eyes to a different way of understanding resistance. It is through our work together that I have looked to Filipino food as a transformative power, a space of healing, and a path to resistance.

HOMECOMING

As my consultant, Dina, and I talk about our feelings of homesickness, for our families back home, and the homesickness from searching for our community, she reflects how relieved she is to have me join her family for a meal. It was rare for her to share a traditional Filipino meal with another member of her community who was not just her family, she contends, and it has made her ecstatic. And I, too, was looking forward to having a sense of familiarity and warmth, as someone who has recently moved from Los Angeles to the Research Triangle.

As I entered Dina’s home, I could smell the familiar smell of steamed white rice that was always reminiscent of my home -- in Los Angeles and in the Philippines. I sat down and a feast of traditional Filipino food was laid out on the table. A big bowl of sinigang is in the center. Sinigang is a stew with pork and vegetables, equal parts salty, sour, and comforting. Two bowls of white rice guarded the big bowl of sinigang. The rice was hot, steamy, and fragrant. Further along the side was an array of lumpia laying atop each other forming a pyramid. Lumpia is a fried spring roll filled with pork and vegetables, usually enjoyed with a sweet chili dipping sauce. Without saying anything, everyone passes each plate of food to each other, taking turns to serve themselves. I smiled at this collectively caring gesture. I then put the bowl of sinigang up to my mouth and it was like being transported to my grandmother’s house in the Philippines. It is a Sunday afternoon and my entire family and I are gathered at the table for a nutritious lunch- my uncle is loud and boisterous, and my aunt is sipping her soup hungrily. My cousins are three feet tall, so they get up from their chairs to reach the food. My grandfather uses his hands to eat a handful of the dry food and switches to his spoon when he wants to take a sip of the sinigang. This moment made me realize how much food plays a tremendous role in preserving memory, culture, and identity, regardless of where one lives, a diasporic homecoming, as anthropologist Martin Manalansan argues (2013). It is this imagined idea of homecoming through senses, emotions, and other embodied experiences. Thus, “coming home occurs not only in the moment of physically setting foot on homeland soil; it also can be through emotion-filled and memory-ridden food events in the “elsewhere”’ (2013: 292). In breaking bread with Dina and her family in the middle of Youngsville, North Carolina, we were transported back to our homeland. At the same time, this communal feast allowed us to form our community, regardless of our feelings of invisibility in the South. Being able to break bread with traditional “ethnic” food becomes more than sustenance for marginalized communities- it becomes an homage to their roots. These imagined homecomings are integral for displaced communities. Further, these sensory experiences of homecoming expands the notion of diasporic return, as food is easily the most accessible avenue with which one can initiate a return.

In a similar vein, Don, a second-generation Filipino from Charlotte, NC, shares his connection to Filipino culture through the food. He contends, “Food is really important to me culturally. My parents were interested in assimilation, but they still wanted to retain our ethnic identity through our food.” Echoing the experiences of many immigrants, assimilation felt like a requirement to fully integrate into American society. In Don’s case, although his parents wanted to assimilate, they wanted to hold one thing close to their heart that they would preserve, and that was the food. Orquiza’s study on the utilization of food as an assimilating tool in the Philippines during the American occupation is a vital point in history to contextualize the relationship between food and assimilation. Filipino food symbolized “the dirtiness, barbarity, and backwardness of the Philippines—and the need for American reform,” according to many American soldiers/governors in the Philippines (Orquiza 2020: 31). Though Filipino food was a target for erasure, the community has persisted in preserving authentically Filipino recipes for generations to come. The importance of food in the community becomes so much more than sustenance, for it is a point of resistance in history, and in the everyday. Don recounts that his mother actually created her own recipe of Laing from collard greens in substitute for taro leaves, because she could not find taro leaves in any of the local supermarkets. This fusion symbolizes cultural preservation, and how food can be one element with which one crosses the path to resistance. Further, this also opens up a conversation about fusion in Southern cuisine, as collard greens are a classically Southern delicacy. What does it mean for collard greens to be used as a substitute for a traditional Filipino dish? What does it mean for collard greens to not be prepared as an iconic Southern dish? In “Beyond Authenticity,” Martin Manalansan argues that authenticity, especially when it comes to food, is a kind of “constructed settled-ness” (2013: 15). When it comes to Filipino food, and immigrant food in general, he asks us to consider deconstructing ideas of authenticity. Oftentimes, this discourse is a messy terrain which produces subjective and open-ended answers. With this in mind, Don’s mother using collard greens to prepare her dish does not make it any less Filipino. This discourse on authenticity and fusion does go into the messy terrain of cultural ownership, especially when it comes to food gentrification. Food journalist Clarence Page reflects on the “Columbus-ing” of collard greens when it was hailed as “the new kale” in popular food magazines. “Columbus-ing” alludes to the gentrification of cultural symbols, removing all points of contact from the culture itself to ensure mass commodity to the white audience. To go back to hooks’ essay, “On Eating the Other,” she talks about the ways in which white mass culture profits off of interactions with the Other, fueling an ‘imperialist nostalgia’ that is embedded in the white supremacist capitalist patriarchy (2014:25). To use food as a lens, is to honor the people and communities that have created these recipes. To honor Southern food is to also honor black food and black communities.

CONCLUSION

One cannot talk about the South without black history, for this culinary inheritance has its roots in enslavement. These roots are explored in Jessica B. Harris’ High on the Hog, as Harris traces the history of African dishes introduced into American food culture, forcing us to look deeper into what food inherently symbolizes for marginalized people. Further, Harris prods us to reconsider old notions of the South, as well as Southern food, as stereotypical notions of Southern food inherently objectifies and disrespects black culture and black history through inappropriate brandings that embody black Southern cooks like the brand Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben, to name a few. Harris quotes Ebony food editor, Freda DeKnight, in her piece, Date with a Dish: “It is a fallacy, long disproved that Negro cooks, chefs, caterers, and homemakers can adapt themselves only to the standard Southern dishes, such as fried chicken, greens, corn pone and hot breads” (2011: 11). These stereotypes of the South as well as Southern food perpetuate the myths of the South as monolithic, and further, it takes away the intricacies and depth of African food culture. Further, images of the enslaved Black cooks, especially black women, are also stereotypical of old ideas of the South. As Zafar continues, “Historians note that real-life Black female household chefs were relatively rare in antebellum America, yet Harriet Beecher Stowe’s best-selling Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), with its detailed depictions of two Black women cooks, fixed that persona in the nation’s consciousness” (2019: 2). This opens a bigger critique on how we define Southern food, and how we stereotypically attach these ideas to black women’s domesticity. Further, these stereotypes also tell us about how emblematic ideas of the South are centered on food, and food-making rather than place-making and survival. Culinary historian Michael Twitty writes,

I dare to believe all Southerners are a family. We are not merely Native, European, and African. We are Middle Eastern, and South-Asian and East Asian and Latin American, now. We are a dysfunctional family, but we are inheritors of a story with many sins that bears the fruit of the possibility of ten times the redemption. One way is through the reconnection with the culinary culture of the enslaved, our common ancestors, and restoring their names on the roots of the Southern tree and the table those roots support” (2017: 12).

To continue this thread of deconstructing normative ideas of the South, we must continue to study the South, not through the dominant literature, but through the people who have made a home within this region, each and every single community that has created their version of the South.

In The Edible South, Marcie Cohen Ferris writes, “Southern food is many things to many people—a vast world of meaning and symbolism and plain old eating to generations of Southerners and visitors to the region” (2014: 25). Indeed, Southern food is iconic to native Southerners as well as to outsiders looking in. Cornbread, Barbecue, Grits, Fried Chicken - these are often what people think of when they hear, “Southern food.” As Lisa Lefler contends, “Southern foods help identify various regions, ethnicities, histories, and ecosystems. They are the substance of memories of fishing, hunting, planting, gathering, harvesting, “putting up,” and of family gatherings where foods were prepared and consumed. Even the vessels in which foods were cooked are artifacts of culture and place” (2013:3). Southern food then takes on a meaning of its own, one that relies heavily on community. This region’s complex relations of power and place affect the ways in which it redefines itself. From its “old white-and-black” past, to now home to diverse communities, the South becomes more of a state of mind rather than a time capsule. However, this transformation is not over yet. These webs of power and space affect the ways in which marginalized communities create their own spaces within this region. The question of place, space, and identity will always be tied into the South. Even with ever-expanding notions of what constitutes “Southern,” many things still get left behind. I argue that Filipino foodways offer a lens through which to challenge the idea of the South as a monolith. It is through including these experiences and traditions that we can attempt to define a “new Southern Studies,” one that reflects all communities residing in this region. This study of Filipino foodways in the South allows us to open up the conversation about Southern Filipino American experience.

In my conversations with Trisha, she expressed wishes for more voices like ours - not just within Southern Studies, but across many fields and disciplines. To her, this is what reparations mean for our people. Additionally, foodways should be considered as a path to these reparations. Ideas of history-making should not be exclusive to Western modes of thinking, as it devalues the richness of traditions being passed within communities of color. Filipino Americans in the South create their own placement and visibility in the South in all forms, but especially through the food they make in their own homes as well as the restaurants/eateries in this area.

It is also important to understand that not all feelings that arise from the gustatory experiences in relation to food are necessarily pleasant, as they can confront uncomfortable feelings within marginalized communities. As Rhesa contends, “I remember when I was really little, when we were still at Dorothea Dix, we would have Filipino food a lot more. As my siblings started to get older, they did not want anything to do with Filipino food. My youngest sister even refused to eat rice (laughs). She said she did not want to be Filipino, and we had rice at every meal.” Rhesa’s siblings refusing to eat Filipino food is evidence that “ethnic” foodways can sometimes generate a conflicting experience. As Manalansan argues, “issues and meanings of food are not always pleasant. In fact, to insist on the positive aspects of food consumption ignores the blind spots in our critical understanding of the complicated ways in which people, particularly immigrants, relate to their homelands and their cuisines” (2013: 298). Though the consultants I have worked with have argued for the close relationship of food to their ethic and cultural roots, it is also worth noting the opposite of these experiences. For the Filipino Americans consultants in the Triangle whom I have worked with, food can be a space of visibility and resistance. As I continue this project, I plan to explore these layered meanings more deeply, including the discomfort that these gustatory experiences can bring.

I want to end with an anecdote that describes my determination to find a seat at the table that is Southern Studies and American Studies. As I peruse through the books in a popular, hip bookstore-cafe at Chapel Hill, I cannot help but overhear a conversation between two of the bookstore workers with one customer, who I noticed was an Asian American woman. The customer asks, “Do y’all have a section on Asian American authors?” to which one of the workers frantically accommodate with “Oh, they should be here somewhere…” followed by a walk-through of the section on “social justice.” The workers tried, to no avail, it seems. One worker puts their hand up to say “Yeah, that’s weird we don’t have any…” I chuckle at this exchange, because it somehow feels like invisibility follows Asian Americans everywhere -- even in the form of books! This is why I do the work that I do here in the Research Triangle in North Carolina. It is my hope that no Asian American person would have to stand in a bookstore naming popular Asian American authors to folks who have not even the slightest clue who they are, or even care to. Filipina fiction writer Cinelle Barnes (2020) in her introduction for A Measure of Belonging calls on people of color to fight back against invisibility and the mystification of the South. She retorts, “Small is the South that saves its best resources to perpetuate a cultural homogeneity. And small are the books about this region that refuse the voices and narratives of people of color… there is not nothing for me here. And there is not nothing for other people of color” (2020: xiv).

In this work, my consultants and I have worked through the beauty and the pain that comes with our positionalities as Filipinos in the South. We laughed about our family’s odd food traditions, told stories about our childhood, and found a way to cope through the pain of being singled out because of our race. My consultants have also helped me understand the precarity of my position in a predominantly white institution like UNC Chapel Hill. Never in my whole life have I ever felt as hyper-visible and invisible. Through this reckoning, I have also never in my whole life held tighter to my community in a place so far from home - Don, Trisha, Dina, and the family and friends they introduced me to; to the workers at MediterrAsian who smile at me like a long-lost friend when I speak to them in Tagalog; to my wonderful colleagues who now consider Filipino American voices and history in their work as well: maybe the inclusion of Asian American voices, let alone Filipino American voices, in the landscape of the South will not happen overnight, but as they say here, I’ll take my sweet ol’ time fighting for it.

References:

Behar, R. (1996). The vulnerable observer: Anthropology that breaks your heart.

Cohen-Ferris, Marcie. (2014). The Edible South: The Power of Food and the Making of an American Region.

Cruz, A. (2016). “The union within the union: Filipinos, Mexicans, and the racial integration of the farm worker movement.” Social Movement Studies, 15(4), 361–373. https://doi-org.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/10.1080/14742837.2016.1149057

Cordova, Fred. (1997). “Foreword,” in Filipino Americans: Transformation and Identity, ed. Maria P. P. Root. Thousand Oaks, C.A.: Sage Publications.

De, Jesus. M. L. (2005). Pinay power: Peminist critical theory : theorizing the Filipina/American experience. New York: Routledge.

Diner, H. R. (2001). Hungering for America: Italian, Irish, and Jewish foodways in the age of migration. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Douglas, Mary. “Deciphering a Meal.” Daedalus 101, no. 1 (Winter 1972): 61–81. “Standard Social Uses of Food: Introduction.” In Food in the Social Order: Studies of Food and Festivities in Three American Communities. Edited by Mary Douglas. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1984, 1–39.

Espina, Marina. (1988) Filipinos in Lousiana. A.F. Laborde & Sons. New Orleans.

E. San Juan Jr. (1994). “The Predicament of Filipinos in the United States: “Where Are You From? When Are You Going Back?” in The State of Asian America: Activism and Resistance in the 1990s. ed. Karin Aguilar San-Juan (Boston: South End) 206.

Fernandez, Doreen. (2002). ‘‘Food and War.’’ In Vestiges of War: The Philippine-American War and the Aftermath of an Imperial Dream, 1899–1999, ed. Angel Velasco Shaw and Luis H. Francia, 237–46. New York: New York University Press.

Harris, J. B. (2011). High on the hog: A culinary journey from Africa to America. New York: Bloomsbury.

Herman, B.L. (2009). “Drum Head Stew: The Power and Poetry of Terroir.” Southern Cultures 15(4), 36-49. doi:10.1353/scu.0.0081.

Ho, J. (2004). Consumption and identity in Asian American coming-of-age novels. Taylor & Francis Group.

hooks, . (2015). Black looks: Race and representation.

Interview with Anna-Rhesa Versola, 18 April 2017, R-0957, in the Southern Oral History Program Collection #4007, Southern Historical Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Ku, R. J.-S. (2013). Eating Asian America: A food studies reader.

Lefler, L. J., & Southern Anthropological Society. (2013). Southern foodways and culture: Local considerations and beyond. Knoxville, TN: Newfound Press, University of Tennessee Libraries.

Mabalon, D. B. (2013). Little Manila Is in the Heart: The Making of the Filipina/o American Community in Stockton, California. Raleigh, NC: Duke University Press.

Mabalon, Dawn and Rico Reyes. 2008. Images of America. Filipinos in Stockton. Mount Pleasant: Arcadia Publishing.

Mahuika, N. (2019-11-14). Rethinking Oral History and Tradition: An Indigenous Perspective. : Oxford University Press. Retrieved 9 Mar. 2022, from https://oxford-universitypressscholarship-com.libproxy.lib.unc.edu/view/10.1093/oso/9780190681685.001.0001/oso-9780190681685.

Manalansan, Martin, IV. (2013) “Beyond Authenticity: Rerouting the Filipino Culinary Diaspora” in Eating Asian America: A Food Studies Reader. NYU Press.

Nadal, K. L. (2011). Filipino American psychology: A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice.

Ocampo, A.C. (2013). “Am I Really Asian?”: Educational Experiences and Panethnic Identification among Second–Generation Filipino Americans. Journal of Asian American Studies 16(3), 295-324. doi:10.1353/jaas.2013.0032.

Orquiza, R. A. D. (2020). Taste of Control: Food and the Filipino Colonial Mentality Under American Rule.

Page, C. (2014, Oct 15). “The gentrification of collard greens.” Chicago Tribune. Retrieved from http://libproxy.lib.unc.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/gentrification-

collard-greens/docview/1611478475/se-2?accountid=14244

Pierce, L. “Not Just My Closer: Exposing Familial, Cultural, and Imperial Skeletons,” in Pinay power: Peminist critical theory : theorizing the Filipina/American experience. New York: Routledge.

Rafael, V. L. (2000). White love and other events in Filipino history. Durham: Duke University Press.

Twitty, M. (2017). The cooking gene: A journey through African American culinary history in the Old South.

Zafar, R., & Zafar, R. (2019). Recipes for respect : African American meals and meaning. University of Georgia Press.

[1] In Nadal’s landmark study, Filipino American Psychology: A Handbook of Theory, Research and Clinical Practice, he argues that the socio-cultural experiences of Filipinos are misrepresented in research, and that they have disparate experiences in education, income, and representation compared to other Asian American groups thus, the conception of the model minority myth (108). Regardless of location, Filipinos experience both hyper-visibility and invisibility. Hyper-visibility for their otherness is etched onto their skin, and invisibility, because their histories are simply homogenized.

[2] Sociologist Adrian Cruz reveals Filipino farmworkers as “overlooked central actors” within farm labor activism in the 1960s. See “The union within the union: Filipinos, Mexicans, and the racial integration of the farm worker movement”

Comments